Articles

Creating the Optimal Back Arch in The Snatch & Clean

April 30 2018

April 30 2018

Back extension is a touchy subject, and has been for as long as I can remember. We even used to have an exercise called a hyperextension… and then suddenly that was too frightening to use anymore, and we had to call it a back extension. In the next few years, we’ll probably have to change it again to something even more benign and reassuring, like happy core wiggles.

The arch of the back is an important element to successful snatches and cleans. There have been some remarkably good weightlifters throughout the years who have defied reason and lifted world-class weights with terrible back extension (i.e. a lack of it), but like all things in sport, the mere existence of exceptions isn’t reason to mimic them.

Neutral Spine

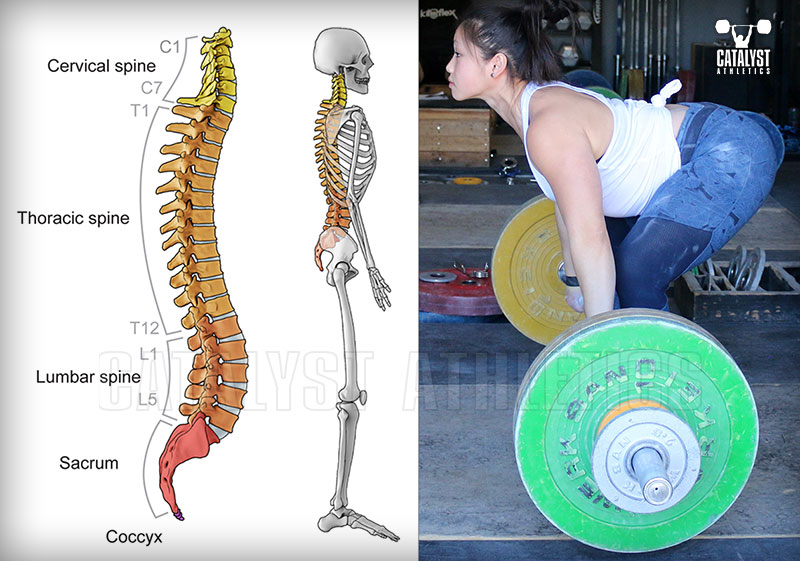

First, I want to address this term: neutral spine. This concept has become so perverted and misunderstood in the last few years that I find I’ve had to reset people’s understanding as a baseline before continuing. A neutral spine is a spine positioned the way it’s anatomically designed to be positioned in a standing posture with no external loading or any other unusual conditions.

This is NOT a straight line! The spine is constructed to exist in a series of curves—the vertebrae are actually wedge-shaped to varying degrees to create these curves. In a neutral spine position, the top and bottom surfaces of each vertebrae are flat against the adjacent intervertebral discs and the next vertebra on either end. In other words, the spine is stacked in a manner that distributes the pressure evenly across the contacting surfaces when you’re standing up.

So many people have been misled on this into believing that neutral spine means a flat spine. In fact, we have a curve in the lower back, in which the spine arches forward (lordosis), an opposing curve in the upper back (kyphosis), and then another lordotic curve in the neck. Straightening the spine from this natural series of curves is NOT neutral, nor is it particularly helpful for much of anything.

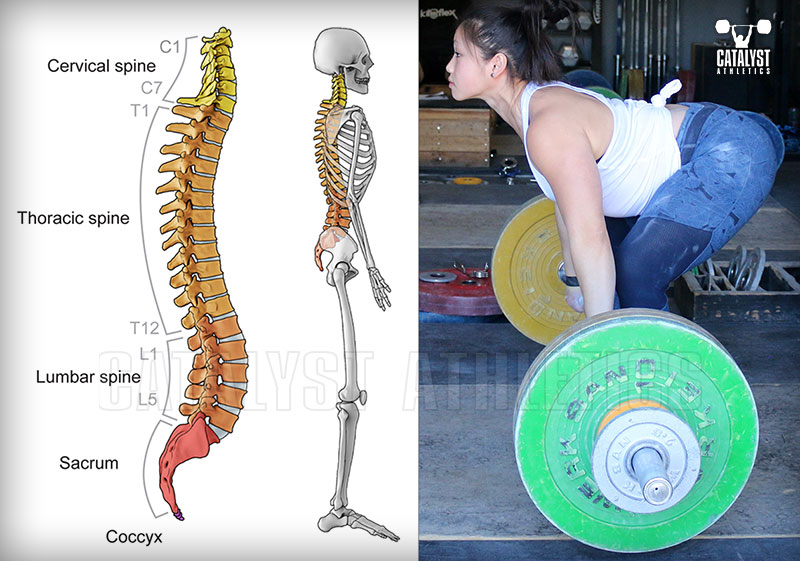

The Optimal Arch for the Pull

The back should be set in complete extension—effectively a single continuous arch from the lumbar to cervical spine. The natural lordotic curve of the lumbar spine should be exaggerated slightly and the kyphotic curve of the thoracic spine flattened as much as possible. The latter is often limited in new lifters with the prevalence of thoracic immobility and stiffness, while the former is often prevented by limited hip mobility. Both need to be addressed and corrected as soon as possible in a new lifter’s development, as the ability to establish a proper back arch is one of the most important fundamental elements in successful lifting.

This arch of the entire back creates the most rigid lever arm possible to transmit the force generated by the legs and hips to the barbell. Such an arch shortens the length of the back slightly, reducing the length of the lever arm the musculature must support and move, and creates the best possible position for the spinal extensor muscles to act on the spine—reduced extension increases their mechanical disadvantage. Rounding of the back can reduce the force to the bar by as much as 15%. In addition, the slight hyperextension acts as a buffer against inadvertent lumbar flexion under load, which is the position that creates the greatest risk for injury for the lower back.

Left: Neutral spine with its natural curves. Right: Complete extension.

The slight exaggeration of the lumbar arch is where people freak out, so let me assuage your fears further if I can. Aside from this being a hedge against a flexion injury and allowing the spinal extensors to better hold the spine’s position, keep in mind the position and movement we’re talking about here: we’re bending over and lifting a weight attached to the end of our spines. In other words, we have a load at the end of a long lever (the spine), which means we’re resisting torque, not compression.

There is some compressive force, including that created by our own bodies to maintain the spine’s position, but nowhere even approaching what the spine would experience if we were standing vertically with a load on top of us (like in a jerk rack position, for example). So a slight exaggeration of the lumbar arch means a bit more pressure at the posterior side of the vertebrae and discs, but the far greater force is in opposition to that pressure—basically trying to pull the posterior sides of the vertebrae apart. As long as we’re leaning forward, this slight increase in lumbar extension past its natural curve is not only not going to harm the back, but it will better protect it.

With regard to the thoracic spine, we’re aiming to flatten the neutral forward curve because that curve makes it harder for the spinal extensors to resist that forward torque. Again, because we’re not dealing with compressive force, but with torque, the shifting of the contact of the adjacent vertebral surfaces isn’t much of a concern.

Unless there is a pre-existing injury or issue with the neck, the head should be upright, which extends the cervical spine somewhat beyond neutral. The Soviets found decades ago that cervical extension increases the overall extension force the back can create; in other words, if the head is upright, the back is stronger in the pull.

The back arch should be reinforced, and maximal rigidity of the trunk ensured, with pressurization and aggressive circumferential muscular tension. It will be easier to take this breath before entering the final starting position, in which the abdomen will usually be compressed to some degree. This is another advantage of a dynamic start—such starts usually naturally create opportunities to take in an unrestricted breath.

The shoulder blades should remain in an approximately neutral position fore and aft, although for some lifters, the shoulder blades will protract to some degree unavoidably in order to allow the lifter to reach the bar in the starting position. The lats should be engaged naturally with the effort to extend the upper back, which will create depression of the shoulder blades. This activation of the lats will also keep the bar in close proximity to the body during the pull when the shoulders are in front of it rather than allowing it to swing away.

The arch of the back is an important element to successful snatches and cleans. There have been some remarkably good weightlifters throughout the years who have defied reason and lifted world-class weights with terrible back extension (i.e. a lack of it), but like all things in sport, the mere existence of exceptions isn’t reason to mimic them.

I’m going to preface the following with this disclaimer: I’m not an orthopedic specialist, a medical professional, or a spinal researcher. If you believe, for whatever reason, that my recommendations are unsafe, by all means, do whatever you want instead. It’s your problem to handle as you see fit. All I can do is assure you that my recommendations are based on experience as a coach and lifter, the documented experience over decades of many other coaches and lifters, and yes, even some research here and there (the kind done by people in the weightlifting world, not in th help, I need to be continuously cradled gently in the caring hands of an adult world).This arch of the entire back creates the most rigid lever arm possible to transmit the force generated by the legs and hips to the barbell.

Neutral Spine

First, I want to address this term: neutral spine. This concept has become so perverted and misunderstood in the last few years that I find I’ve had to reset people’s understanding as a baseline before continuing. A neutral spine is a spine positioned the way it’s anatomically designed to be positioned in a standing posture with no external loading or any other unusual conditions.

This is NOT a straight line! The spine is constructed to exist in a series of curves—the vertebrae are actually wedge-shaped to varying degrees to create these curves. In a neutral spine position, the top and bottom surfaces of each vertebrae are flat against the adjacent intervertebral discs and the next vertebra on either end. In other words, the spine is stacked in a manner that distributes the pressure evenly across the contacting surfaces when you’re standing up.

So many people have been misled on this into believing that neutral spine means a flat spine. In fact, we have a curve in the lower back, in which the spine arches forward (lordosis), an opposing curve in the upper back (kyphosis), and then another lordotic curve in the neck. Straightening the spine from this natural series of curves is NOT neutral, nor is it particularly helpful for much of anything.

The Optimal Arch for the Pull

The back should be set in complete extension—effectively a single continuous arch from the lumbar to cervical spine. The natural lordotic curve of the lumbar spine should be exaggerated slightly and the kyphotic curve of the thoracic spine flattened as much as possible. The latter is often limited in new lifters with the prevalence of thoracic immobility and stiffness, while the former is often prevented by limited hip mobility. Both need to be addressed and corrected as soon as possible in a new lifter’s development, as the ability to establish a proper back arch is one of the most important fundamental elements in successful lifting.

This arch of the entire back creates the most rigid lever arm possible to transmit the force generated by the legs and hips to the barbell. Such an arch shortens the length of the back slightly, reducing the length of the lever arm the musculature must support and move, and creates the best possible position for the spinal extensor muscles to act on the spine—reduced extension increases their mechanical disadvantage. Rounding of the back can reduce the force to the bar by as much as 15%. In addition, the slight hyperextension acts as a buffer against inadvertent lumbar flexion under load, which is the position that creates the greatest risk for injury for the lower back.

Left: Neutral spine with its natural curves. Right: Complete extension.

The slight exaggeration of the lumbar arch is where people freak out, so let me assuage your fears further if I can. Aside from this being a hedge against a flexion injury and allowing the spinal extensors to better hold the spine’s position, keep in mind the position and movement we’re talking about here: we’re bending over and lifting a weight attached to the end of our spines. In other words, we have a load at the end of a long lever (the spine), which means we’re resisting torque, not compression.

There is some compressive force, including that created by our own bodies to maintain the spine’s position, but nowhere even approaching what the spine would experience if we were standing vertically with a load on top of us (like in a jerk rack position, for example). So a slight exaggeration of the lumbar arch means a bit more pressure at the posterior side of the vertebrae and discs, but the far greater force is in opposition to that pressure—basically trying to pull the posterior sides of the vertebrae apart. As long as we’re leaning forward, this slight increase in lumbar extension past its natural curve is not only not going to harm the back, but it will better protect it.

With regard to the thoracic spine, we’re aiming to flatten the neutral forward curve because that curve makes it harder for the spinal extensors to resist that forward torque. Again, because we’re not dealing with compressive force, but with torque, the shifting of the contact of the adjacent vertebral surfaces isn’t much of a concern.

Unless there is a pre-existing injury or issue with the neck, the head should be upright, which extends the cervical spine somewhat beyond neutral. The Soviets found decades ago that cervical extension increases the overall extension force the back can create; in other words, if the head is upright, the back is stronger in the pull.

The back arch should be reinforced, and maximal rigidity of the trunk ensured, with pressurization and aggressive circumferential muscular tension. It will be easier to take this breath before entering the final starting position, in which the abdomen will usually be compressed to some degree. This is another advantage of a dynamic start—such starts usually naturally create opportunities to take in an unrestricted breath.

The shoulder blades should remain in an approximately neutral position fore and aft, although for some lifters, the shoulder blades will protract to some degree unavoidably in order to allow the lifter to reach the bar in the starting position. The lats should be engaged naturally with the effort to extend the upper back, which will create depression of the shoulder blades. This activation of the lats will also keep the bar in close proximity to the body during the pull when the shoulders are in front of it rather than allowing it to swing away.

Greg Everett